Guest post by Dr Samantha Heath

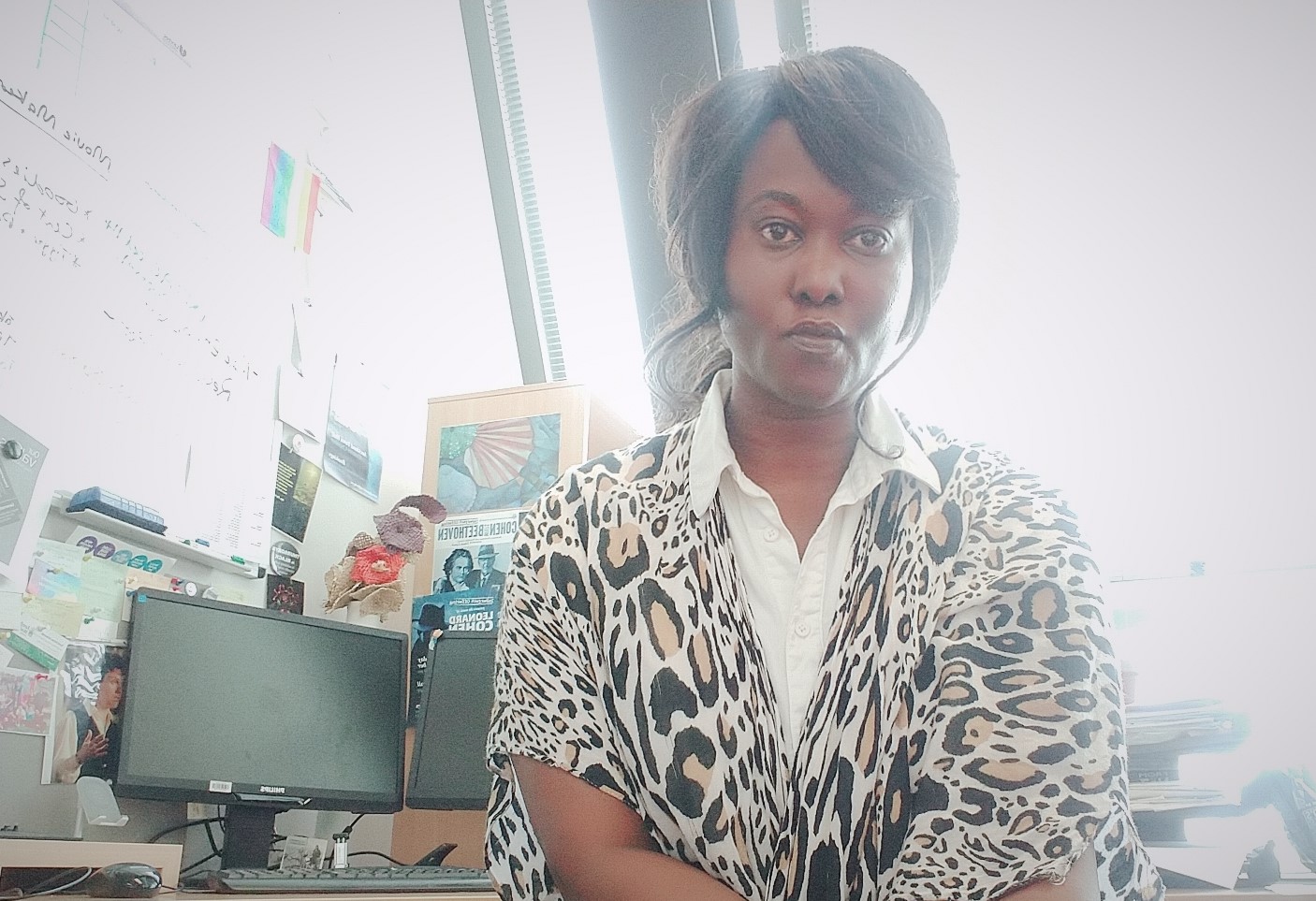

Irene Ayallo, Senior Lecturer in Social Practice at Unitec, Te Pūkenga, has intentionally been working with ethnic migrants and refugee-background communities in Aotearoa New Zealand for several years. She is passionate about issues that significantly affect migrant wellbeing, particularly immigration factors that can contribute to family violence.

Historically, the partnership visa has been the most popular, where one partner will come to New Zealand first and be joined later by the other partner and family. As with all visas, conditions apply. For this type of partnership visa, the holder is tied to the relationship for a two-year probationary period. For ethnic migrant women experiencing intimate-partner violence, it has created conditions in which the person experiencing violence depends on the abusive partner because of their financial situation. For example, in most cases, the visa does not allow for government financial support. This is especially burdensome for ethnic women who do not speak English and have not established a support network.

In 2011, Immigration New Zealand created a special visa category called the Victims of Family Violence Visa. When someone finds themselves in such a circumstance, they can apply for their own immigration status before the two-year probationary period finishes. It was a significant and positive move by the government to provide an option for a work visa or work-to-residence visa. However, despite the availability of these visas, family violence is still prevalent among our ethnic communities and continues to be under-reported. Irene wanted to know why, and she designed a two-part research project. Irene asked Immigration New Zealand for data on who had applied, focusing on the approval and decline rates for the Middle Eastern, Latin American and African (MELAA) ethnic migrant communities for the last ten years. She found that only 10% of visa applications had come from within MELAA communities. This contradicted what she saw in her practice, highlighting that ethnic women did not effectively utilise the additional visa options. Irene’s publication is now included as one of the key readings on this topic, and you can find it here.

In the second part of her project, Irene spoke to women who had applied or attempted to apply for the new visa type. She quickly realised from the interviews that none of those women had applied for the visa independently, because it was too complicated. Most of the women who needed it have little English; consequently, the application process was inaccessible to them. The process was so complex they needed a lawyer to help. However, most women were not working because their existing visa did not allow them to work, so they needed support from Community Law centres to get assistance. Reaching further into this space, Irene has recently extended her ethics approval for the study to include interviews with community lawyers to hear their perspectives on the issue. She is currently analysing her data. In the meantime, she closely monitors the , presented to Parliament by Jan Logie as a member’s bill last September. If passed, the Bill will alleviate some of the current legislative requirements that deter applicants from being able to remove themselves from family-violence situations.

Irene has also curated a research collection to support her ongoing work with the community. Now up to about 500 pieces, her community research partnership has provided a one-stop resource (which you can find here) for practitioners to find information that could help to support the community in a practical way. Response to the resource, launched in 2021, has been positive, especially from postgraduate students across Aotearoa New Zealand. It has been an excellent research outreach initiative and lately has seen Irene delivering a webinar series. She is proud of the connections she makes to ensure that participatory action research promotes collaboration, accountability and social change.