Guest post by Dr Samantha Heath

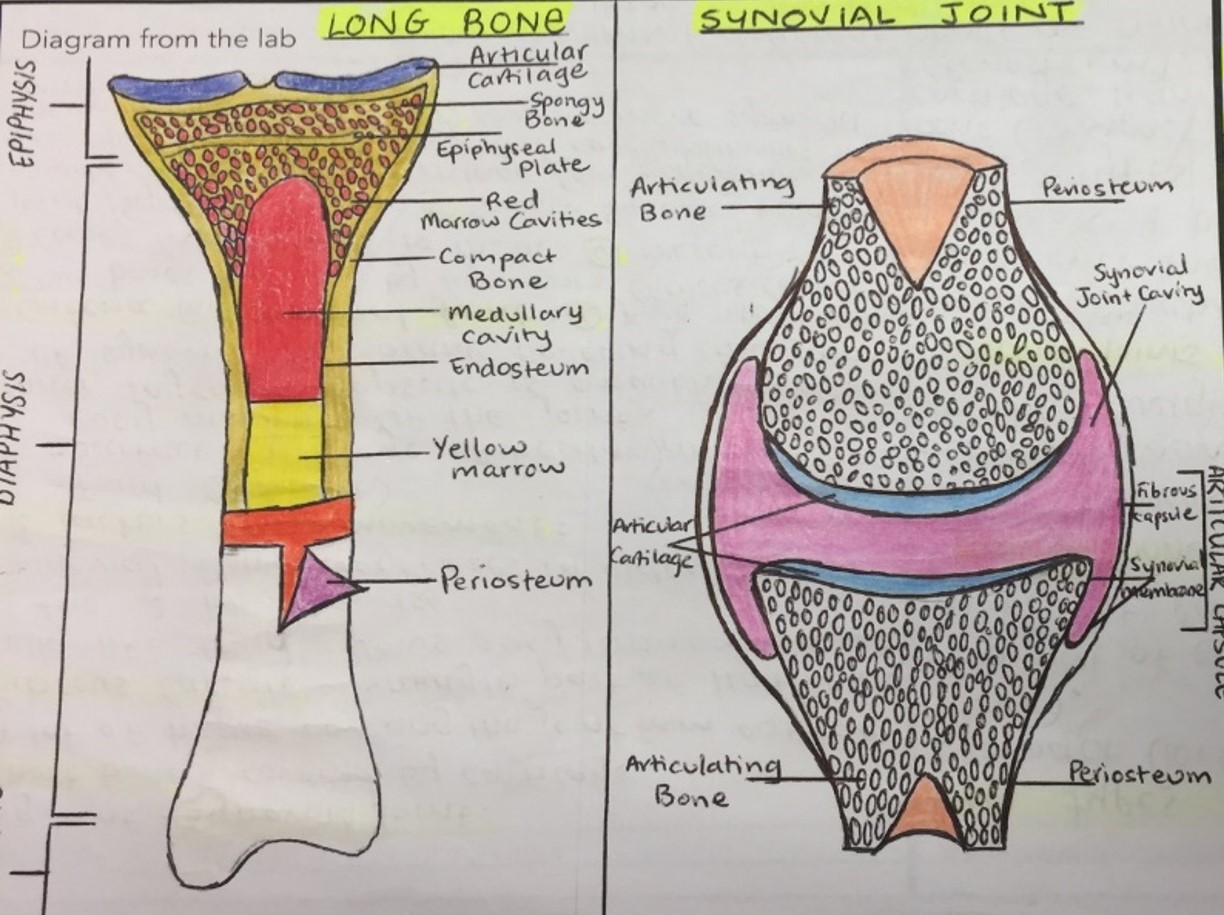

If you asked my colleague Dr Joseph Aziz, a Senior Lecturer in Healthcare at Unitec’s School of Healthcare and Social Practice, about the importance of drawing as a form of communication in healthcare, I know he would entertain you with a fascinating history, beginning with stories about ancient Egyptians and their use of illustration as a means to detail understanding of human anatomy. He would also likely tell you about Galen of Pergamum (120–300 A.D.), who for almost 15 centuries was the authority on human anatomy, having written one of the first human anatomy texts – based entirely on his dissections of the Barbary ape! Joseph would probably include the work of Leonardo DaVinci who, as perhaps the greatest anatomist to have ever lived, took up his craft simply to improve his art, paving the way for Andreas Vesalius, the father of modern anatomy. In his turn, Vesalius’ innovation in teaching human anatomy using dissection, observation and drawing performed by students corrected the misunderstandings created by Galen’s assumption that apes and humans were anatomically identical. Together, these pioneers created a style of teaching human anatomy that has endured well into the 21st century; the exquisite detail in Frank H. Netter’s illustrations are familiar to generations of students.

The value of observational and drawing techniques in anatomy and physiology education for healthcare professionals cannot be emphasised enough. Comprehensive understanding is essential as a foundation for the development of health assessment and caring skills. Without it, there is a lack of depth to the grasp of the patient context. Yet, when drawing competes with digital technologies to support student learning, Joseph and I have observed that drawing is infrequently practised. Indeed, in one early 2020 examination where students were asked to draw and label a human anatomy diagram, marks were extremely low for the section. Joseph and I were curious about whether our nursing and medical imaging students could be encouraged to use drawing to ‘see’ the detail of human systems and whether this would impact on learning anatomy and physiology.

We showcased the learning strategy to first-year students in the first semester of their courses in 2020 with a view to evaluating their experience later on. We used class time to encourage drawing on the giant whiteboards in our collaborative learning space. This gave us the opportunity to assist students to ‘observe’ particular aspects of anatomy and to correct any misunderstanding. We saw how students worked together around the drawing activities. They evaluated the experience positively, remarking on how the interactivity of drawing was a more productive way to learn than by reading or looking at pictures – it certainly appears that students understand this relevance to their clinical practice. In their examination, the second cohort of students performed better than expected, with 55 out of 97 completing a ‘draw and label’ question with no errors and a further 13 completing the same question with a single error, a significant improvement on the previous 2020 results. Our early evaluation of the teaching strategy shows promise, and this year our challenge is to develop a research design to put to the test our hunch that drawing really does work.

April 30, 2021 at 8:50 pm

If you are A&P instructor! So the easy way to communicate with your students is to draw you topics. This is very effective in term of imagination and memorisation as anatomy is 3D subject need more brain space to remember each structure. Health care students are target goal for A&P subject, as they need to understand the basic concepts for anatomical details of human body. Drawing is the easiest way to hit your target with your students.