Guest post by Dr Samantha Heath

Navigating the vagaries of our current health system and accessing the right professionals and treatment can be a difficult job on any given day. Add to this mix being Deaf, having a mental health problem and using sign language as a preferred means of communication, and you wouldn’t be surprised to learn that there are significantly more challenges in accessing assistance.

In the early part of the current lockdown, I was privileged to spend some Zoom time with Dr Geoff Bridgman from Unitec’s School of Healthcare and Social Practice. He knows more than most about the issues for Deaf, having collaborated on research projects with the Deaf community for many years. In this latest study, Geoff and co-authors Rachel Coppage, Catriona Sainsbury and Sarah-Marie Goodwin have explored the experiences of 12 Deaf with mental illness. The research was undertaken by the Coalition of Deaf Mental Health Professionals.

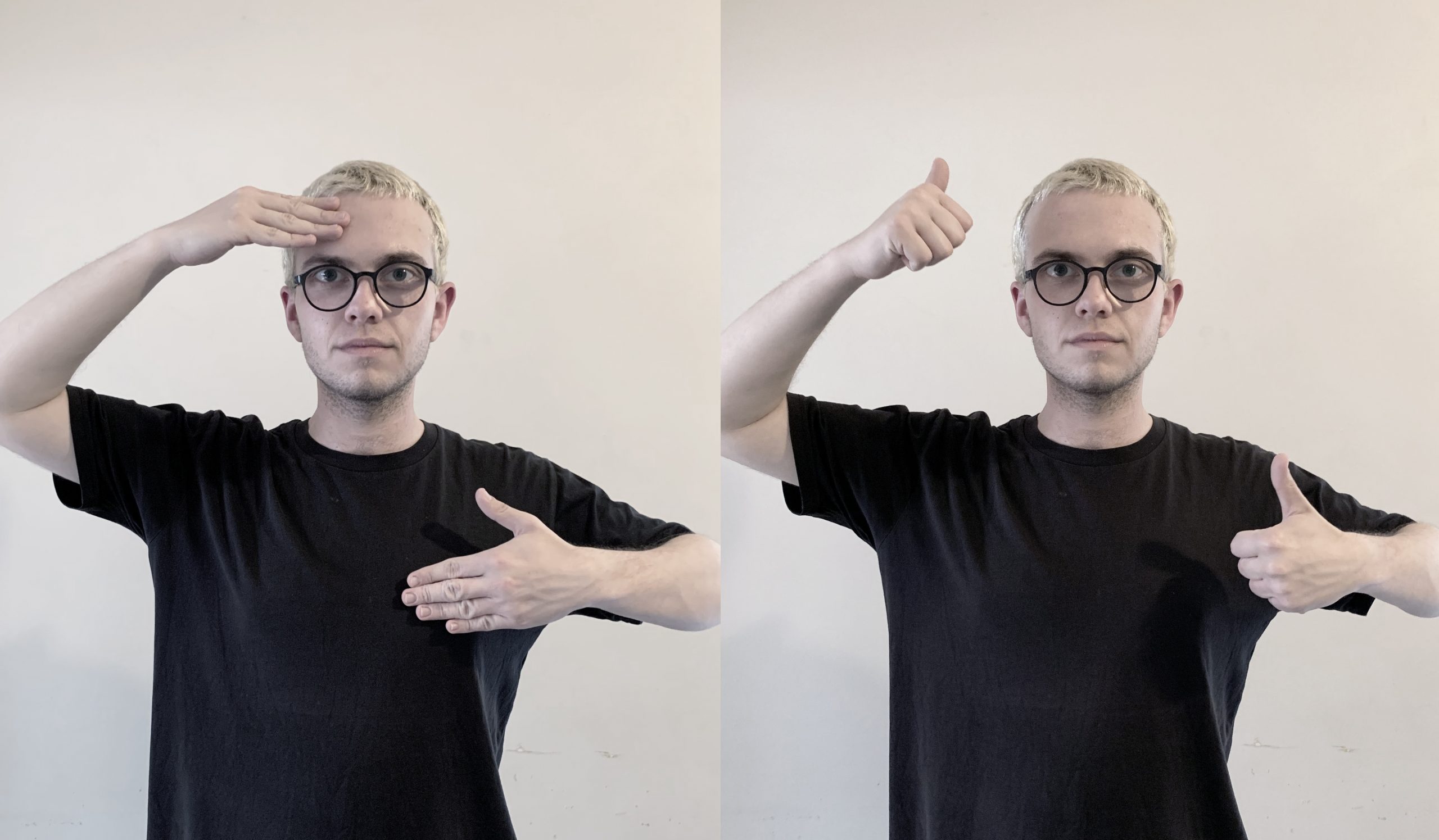

Geoff explained to me some of the difficulties experienced by Deaf that contribute to the need for mental health support services, for example, how being Deaf can lead to isolation and marginalisation across the lifespan. In their report, the researchers have also highlighted the way in which signing is treated as a signed version of English, rather than as a grammatically distinct native language and an expression of Deaf culture. This denial of Deaf cultural identity has massive impact on mental wellbeing. Most Deaf are born into hearing families who often struggle of give their Deaf child access to Deaf culture and language – a struggle that can often lead to abuse, neglect, discrimination and bullying. It’s no surprise, then, that this timely research has illuminated the extraordinary difficulties faced by Deaf needing mental health support.

The researchers found that Deaf often have unexplained or misdiagnosed mental illness. Deaf are frequently categorised as having schizophrenia, personality disorder or depression rather than the more relevant post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) arising from abuse in homes, foster care, schools and in the community. Incorrect diagnoses have meant that some Deaf have been wrongly medicated or incarcerated as a result. Reflecting on services available for Deaf provides some assistance in understanding how this situation arises. About 4500 people in New Zealand identify as Deaf and use New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL) as their preferred method of communication. When Deaf access mental health services they require sign language interpreters or, better, signing mental health professionals. There are surprisingly few people who can fulfil this role; further, there is no national framework or training for the delivery of Deaf mental health services and the vast majority of DHBs have no Deaf-specific service. ACC-funded counselling and psychotherapy does help, but NZSL interpreters have to be part of the therapeutic relationship and become a trusted third party, often over several years, and there are inevitably disruptions in the service. Clearly, there is much more service development to be done to support the Deaf community.

As the current government follows through on the intention to reorganise health into a national service that can reduce the current inequities in health services across DHBs, there is hope that the recommendations from this research can be addressed. These include creation of a nationally co-ordinated framework that delivers a structure for Deaf mental health and addiction services; the training of signing mental health professionals, including Deaf professionals and mental health interpreters; and a stronger system of education-led support for parents of Deaf children, whose wellbeing may depend on an increased engagement with the Deaf community and Deaf culture.