by HELENE CONNOR, JANE BRUNING and KSENIJA NAPAN

by HELENE CONNOR, JANE BRUNING and KSENIJA NAPAN

ABSTRACT

This paper reflects on Positive Women’s twenty five years as a successful community development response to supporting women and families living with HIV or AIDS. The paper focuses on the community development philosophical underpinning of Positive Women that have driven the organisation since its inception in 1991. Positive Women has actively advocated for social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities, all central to community development.

INTRODUCTION

This paper reflects on Positive Women’s twenty-five years as a successful community development response to supporting women and families living with HIV or AIDS. It also offers an inspirational example of how blurring the lines between professional social work, community development and peer support can create transformation in people’s lives and in the communities where they live and work.

Aotearoa New Zealand has a relatively low prevalence of women living with HIV or AIDS. However, the position of women with HIV remains marginalised and many report feelings of stigma, isolation and prejudice (Bruning, 2009). In 1991, social worker and community developer Judith Ackroyd initiated the not-for-profit organisation Positive Women, in order to support women and their families living with HIV or AIDS. Judith was joined by Suzy Morrison and a small group of women from the community, who worked to build the capacity of Positive Women. In 2016, Positive Women celebrated its 25th birthday, and acknowledged the community development response that has enabled the organisation to support those women who represent the invisible face of the HIV and AIDS epidemic.

This paper focuses on the philosophical underpinning of community development that has driven the organisation since its inception in 1991. Positive Women has actively advocated for social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities – all central to community development. The empowerment of women living with HIV through projects such as its Destigmatisation Campaign, launched in 2008, and the 2014 campaign promoting the female condom, have been at the heart of its community and activism.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF HIV/AIDS IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND

Aotearoa New Zealand meets the UNAIDS/WHO (2016) criteria for a ‘low-level’ HIV and AIDS epidemic, as infection is largely confined to individuals with higher-risk behaviour and has not consistently exceeded five percent in any defined subpopulation. On this basis Aotearoa New Zealand has chosen to focus on high-risk groups and behaviours in their HIV and AIDS policies, resulting in a strong focus on men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) and African communities (AEG, 2009). This continued focus on high-risk groups has further marginalised and stigmatised MSM and African communities and has also isolated women who do not belong to these groups (AEG, 2009). While the heterosexual spread of HIV is relatively limited there are, however, a significant number of heterosexual people living with HIV in Aotearoa New Zealand, a factor which appears to be repeatedly ignored or treated as something of insignificance (Bruning, Connor & Napan, 2013).

Initially, the government’s response to HIV and AIDS in Aotearoa New Zealand was slow and restrained (Carter, Howden-Chapman, Park, & Scott, 1996). The first suspected case of “acute HIV infection” was diagnosed in 1983 and by 1985 a further five people had been diagnosed with AIDS. All were men who identified as men-who-have-sex-with-men (Dickson, 1998).

During the 1980s, health officials called for the establishment of an AIDS Support Network (ASN) for people living with AIDS. Volunteers were trained to provide homecare and peer counselling, together with peer education, which was available for people living with AIDS. In addition, several grassroots organisations were established. One of these was the Māori HIV prevention group, Te Roopu Tautoko (TRT), which was created in 1988 with a mandate to undertake HIV prevention work among Māori. By the late 1980s, a need for a women’s support network was identified by two social workers (Judith Ackroyd and Suzy Morrison) employed by the Community AIDS Resource Team (CART), a government funded department closely connected with the Infectious Diseases Clinic based out of Auckland Hospital. During this period there was a notable increase in the number of women being diagnosed with HIV, yet this was largely ignored and little attention was given to the unique features of HIV infection in women (Bennett, 2007). Seeing a gap in service need, CART, together with a number of women living with HIV, began the process of establishing Positive Women (Bruning, Connor & Napan, 2013).

From 1985 to year end 2015, a total of 4,392 people are reported to have been diagnosed with HIV in New Zealand. Of these, 699 are women with exposure categories as follows: 572 through heterosexual contact, 14 through intravenous drug use, 10 as a result of being blood transfusion recipients, 20 through perinatal transmission and 83 through other or unknown transmission. The majority (74%) of heterosexual people who contract HIV acquire it overseas. In contrast, 87% of men who have sex with men, who contract HIV, acquire it within Aotearoa New Zealand (AIDS Epidemiology Group, 2016).

Recording the ethnicity of people who have acquired HIV was undertaken in Aotearoa New Zealand only from 1996. Rates have been two to four times higher among Māori, Pacific and Asian women compared to European women. However, these results are based on very low numbers overall (AIDS Epidemiology Group, 2016).

The second-largest group to be diagnosed with HIV in Aotearoa New Zealand is people from a refugee background and migrants, mostly from Africa. Among this group there are 262 men and 270 women (AIDS Epidemiology Group, 2016).

THE GENESIS OF POSITIVE WOMEN INC.

Positive Women is a peer support, community development response to the needs of women and families in Aotearoa New Zealand living with HIV or AIDS. Ife and Fiske (2006) argue that community development work is explicit in its agenda of giving primacy to wisdom existing at the grassroots level, ahead of external experts. This agenda was explicit in the development of Positive Women from its inception. Women living with HIV or AIDS felt the existing service providers did not meet their needs and as a grassroots response established Positive Women, with assistance from the Community AIDS Resource Team, which worked alongside the Infectious Diseases Clinic at Auckland Hospital. Initially, a small group of women got together to provide moral support to each other and it was run on a voluntary basis.

While Positive Women was very much a grassroots response to the needs of women living with HIV or AIDS, in its early period it was partially controlled and managed by the Community AIDS Resource Team (CART). Ife and Fiske (2006) recognise this mode of community development as coming from above, where the development is instigated and controlled externally. A risk inherent in using this model is the exclusion of the people within the community development project (Ife & Fiske, 2006). In the case of Positive Women however, a human rights approach was at its core, which had a clear, comprehensive and practical framework for development. While it had the support of CART and social workers Judith Ackroyd and Suzy Morrison, the intention of Positive Women’s kaupapa was that it be locally active, and value and affirm the wisdom of women living with HIV or AIDS. Eventually, the operational management of Positive Women was handed over to the women themselves, rendering the organisation an ideal case study of community innovation (J. Bruning, personal communication, April 22, 2016). The values inherent in this kaupapa characterise a bottom up approach to community development practice (Ife & Fiske, 2006).

POSITIVE WOMEN: EXEMPLIFYING EFFECTIVE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PRACTICE

Positive Women became an incorporated society in 2000 and continued to be run on a voluntary basis. This change relied heavily on women stepping up to the role of organising meetings, events and activities, when and if they had the time, energy and good health (Bruning, 2009). Chile (2007) argues that good community development practice evolves from a community, defined as a group of people who share some experiences which bind them together. In the case of Positive Women, the common experience that bound the women together in a community was their shared diagnosis of either HIV or AIDS. Chile further argues that a clear understanding of the concept of community is critical for good community development practice at both personal and political levels. Chile outlines three principles which fulfil the needs of ‘community’ at the personal level. These three principles are clearly evident in the development of community within Positive Women.

Chile’s first principle identifies the need for self-awareness and self-identity, which comes from a process of socialisation and feelings of belonging. In her research on stigma and women living with HIV, Bruning (2009) found that a connection with people in similar situations helped those living with HIV to reduce feelings of isolation and stigma and also helped improve self-esteem and coping skills. The peer support, socialisation and feelings of belonging that Positive Women offered to women and their families living with HIV was invaluable, not only for coming to terms with the condition, but also for contesting notions of a ‘spoiled identity’ that many of the women had internalised. As Bruning (2009) discusses, a diagnosis of HIV is a traumatic event which requires continuous adjustment in regards to both psychological and physiological losses. Recalling her own reaction to her diagnosis, she states:

As well as the shock of being told I had AIDS, I remember feeling like I was poisonous. Even today, twenty years on, and even though I can now say it jokingly [‘my poisonous blood’], I feel like I am a danger to society, that I am dirty and contagious, a marked person with a ‘spoiled identity’ (see footnote 1). While this may initially have been a stigma set by society, I took it on and internalized it to the point that I believed it for many years and possibly still do to some extent (Bruning, 2007, p. 6).

The second principle of community development practice that Chile (2007) outlines is the need for a distinct collective identity that the community can take pride in. From its onset in 1991, Positive Women wanted a distinct collective identity that was different from that of support groups for men living with HIV or AIDS. Creating a space for women living with HIV or AIDS was fundamental to this collective identity, as was creating a community which the women could take pride in.

The third principle outlined by Chile (2007) focuses on the need for collective action to protect and promote self and collective identity, which meets a common vision for desired future expectations. A common vision promoted by Positive Women has been to provide a support network for women and families living with HIV or AIDS. Embedded within their collective vision has been a strong desire to raise awareness of HIV and AIDS in the community via educational programmes with a focus on destigmatisation and prevention, predominantly targeting the heterosexual community as they had identified a gap in this area (Bruning, 2009).

In 2004 the collective community identity and common vision espoused by Positive Women was at risk of collapsing after the resignation of the two voluntary coordinators. It was decided the organisation needed to employ a full-time, paid national coordinator to ensure the sustainability of the organisation, and Jane Bruning was appointed to this role in September 2004 (Bruning, 2009). With the appointment of a full-time national coordinator, Positive Women was subsequently better positioned to develop the internal capacity to undertake their collective visions and goals. One of the first actions Jane undertook was to update the data base, which at the time of her appointment included thirty members (women living with HIV). Of these, it was found that five of the members had died, a poignant reality of the Positive Women community group. The membership has now increased to over two hundred, with an affiliated membership (family/partners of members) of over a thousand.

As with many not-for-profit community development organisations, consistent and sustained funding has often been challenging for Positive Women. While the organisation has sought to be as independent as possible, it has conceded that accessing philanthropic agencies for funding assistance has been necessary for its survival. Having a full-time national coordinator significantly improved the financial viability of Positive Women with targeted funding applications. The main funding source has been the MAC AIDS Fund, which donates one hundred percent of its sales from the MAC Viva Glam range of lipsticks and lip glosses to organisations working with people with HIV or AIDS (MAC AIDS Fund, nd; “Beauty: Lipstick power,” 2010). Other significant funding bodies include Foundation North (formerly ASB Community Trust), the Lotteries Grant Board and more recently, the Ministry of Health (see footnote 2). The external funding has enabled the continued employment of a full-time coordinator and has also enabled Positive Women to carry out its campaigns, educational seminars and other programmes (J. Bruning, personal communication, April 22, 2016).

Chile (2007) argues that good community development must also operate at a political level where the community becomes the locale for action and conscientisation. With a full-time and paid national coordinator at the helm of Positive Women, the organisation has been able to address the political level of community development by effectively organising and managing the group and members to undertake action for social change and development via a number of campaigns and educational events. These include presenting a petition to parliament for access to and subsidy of the female condom (FC) in New Zealand. The National Coordinator of Positive Women was invited to speak to the Health Select Committee about their petition and proposal for the FC. A letter was also sent to Pharmac requesting subsidy of the FC as it is currently (2016) out of reach, price wise, for most women. In 2007, Positive Women was the first organisation to release an HIV destigmatisation campaign which focused on women. The aim of the campaign was to get people to look beyond the common stereotypes of HIV. It did this by using the faces and stories of real women living with HIV, showing them as everyday people; mothers, sisters, daughters, grandmothers and wives. It was a multimedia campaign using posters, a targeted promotion through women’s magazines, including an article in the NZ Listener and a poster campaign on the sides of buses in both Auckland and Wellington. Positive Women has advocated for women by being on the implementation and monitoring group for the HIV Antenatal Screening Programme, being part of the review panel on breast- and other feeding options for babies born to women living with HIV, and joining the advisory group for the Sexual Reproductive Health Action plan, to name just a few such activities. Chile (2007) describes this type of active involvement as community development intervention.

POSITIVE WOMEN AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTION

Community development intervention seeks to empower individuals, groups and communities to attain wellbeing though collective action (Chile, 2007). The focus on wellbeing has been an inherent principle of Positive Women’s kaupapa.

An annual event which focuses on wellbeing is the Positive Women Retreat. The first retreat for women living with HIV was held in 1996 at a yoga retreat centre in the Waitakere ranges, Auckland. Twelve women attended and for many it was the first time they had been given an opportunity to talk and share experiences with other women living with HIV in a confidential and safe environment. Social workers Judith Ackroyd and Suzy Morrison facilitated this first retreat. They helped the women feel welcome and supported, doing all of the cooking and cleaning so the women could rest and relax (J. Bruning, personal communication, April 22, 2016). This event encapsulates the type of community development intervention Chile (2007) describes as promoting non-material wellbeing which enhances human dignity, personal security and empowerment.

The annual retreat has recently changed its format as a result of reduced funding and community members’ discussion and dialogue. Held mid-year, it now offers one full-day seminar that is open to the public, as well as two closed seminar days for women living with HIV. The public day is held at the Maritime Room in Auckland’s Viaduct district and is well attended by a wide range of professionals such as doctors, nurses, midwives, dentists and others in the health sector, as well as women living with HIV. The closed retreat is generally held on Auckland’s North Shore and includes a mixture of workshops, skills building and updates on the latest developments in the treatment of HIV and AIDS. The retreat also offers a variety of relaxing natural therapies such as aromatherapy, reflexology, head and shoulders massage and relaxation massage. The workshops and talking circles provide an opportunity for women to talk with their peers, who understand what it is like to live with HIV (Positive Women, 2012). There is a focus on creating an atmosphere of trust and acceptance, enabling the women to share experiences and information. The links between stress and the immune system have been well researched; having an opportunity to de-stress and connect has a significant effect on the functioning of a compromised immune system (Padget & Glasser, 2003).

One of the aims of community development intervention is to empower individuals, groups and communities to realise their wellbeing via collective action (Chile, 2007). The annual retreat is one example of how Positive Women has sought to enhance their wellbeing. Another important aspect of the retreat is that it provides a space for women to ‘come out’ about living with HIV, without fear of being shamed or berated. This is an important consideration, as many of the women have deeply embedded feelings of guilt, shame and fear, and do not necessarily believe they are entitled to wellbeing. Talking about living with HIV can be a liberating and empowering experience, and the annual retreats have been pivotal in helping women living with HIV to not only talk openly about living with HIV, but also contest discourses of stigma and discrimination. For the participants in the retreat there is a sense of connection and relationality which can be framed as what Mackay (2014) terms ‘the art of belonging’. For Mackay, the ‘art of belonging’ requires tolerance, forgiveness, acceptance of imperfections and nurturance of those communities which sustain us. The retreat makes space for all of these elements to come together at both an individual and collective level.

In their research about women living with HIV/AIDS and a community-based HIV/AIDS service organisation in Massachusetts, DeMarco and Johnsen (2003) also found that retreats are an important aspect of wellness planning for HIV-positive women. As with the Positive Women’s retreat, the Massachusetts women also incorporated information about mind-body medicine, the effects of stress on the immune system, skills-building, activities for stress reduction, and an update on conventional treatment strategies. Both groups also felt it was important to have a trained facilitator present because of the frequently painful discussions that occurred when the women shared traumatic experiences. As with Positive Women, the Massachusetts community-based group also found the retreat was an important place to discuss the way forward and issues of significance to the group (DeMarco & Johnsen, 2003). Similar themes that emerged from both retreats include concerns about younger women at risk in the community, living with a chronic illness, and planning educational seminars for members and the general public (DeMarco & Johnsen, 2003; Positive Women, 2012).

Women living with HIV are often a hidden and hard to reach group, particularly those women who live outside of the large centres. Many women living with HIV also have care-giving responsibilities for their children and partners. Some have partners and children who also have HIV and often the care of loved ones takes precedence over their own self-care. The annual retreat is one way women living with HIV throughout New Zealand can have some respite from care-giving, and also become involved in the organisation by attending the AGM which is held during the retreat.

Financial capital and adequate income are necessary elements in good community development practices, which seek to promote equality and equity and the right to participate (Chile, 2007). Funding is thus sought to pay for the accommodation and other costs, and to provide transport assistance for women living with HIV who live outside of Auckland. As Chile (2007) argues, good community development practice must abandon the myth that only the poor and disadvantaged benefit from such practice. Rather, the role of community development is to ensure all citizens and high-needs groups attain access to the benefits of good practice, community wellbeing, cohesive networks and community-based initiatives.

POSITIVE WOMEN AND ITS COMMUNITY VISION

Over the past twenty-five years, Positive Women has attained its vision for a viable community-based HIV and AIDS service organisation via collaborative processes of decision making and ‘ownership’ by the community living with HIV. Local leadership was established at the community level by creating a full-time coordinator role, a decision which came out of the Positive Women retreat AGM in 2004. The vision and the actions of the organisation are derived through collective decision making with an awareness of the issues which affect the wellbeing of its members. An aspect of this vision has been to collaborate with other organisations, such as Body Positive (see footnote 3), NZAF (see footnote 4), and INA (see footnote 5). This collaboration and sharing of resources is the essence of whakawhānaungātanga, one of the principles that in Aotearoa New Zealand transcends differences by creating a common vision and strategy.

Marama Pala, the Kaiwhakahaere (Executive Director) of INA is also a member of Positive Women and, in 1993, was the first Māori woman to disclose her HIV status (INA, 2008). Marama is passionate about Māori living with HIV having access to resources, and is a strong advocate for Māori and other indigenous peoples. Positive Women and INA collaborate to support wahine Māori, and Marama has assisted Positive Women on formal occasions when it has been appropriate to open with powhiri and mihimihi.

The whakawhānaungātanga that Positive Women has cultivated with Marama Pala and INA has been a genuine attempt to foster bicultural understanding and acknowledgment, but it is woefully inadequate as there is no internal practice of Māori tikanga, and Positive Women Inc. relies on INA to do the public ‘formalities’. This latter practice is tokenism to some extent, although with the best intentions. As the two organisations are often at the same meetings and events, this arrangement no longer works very well. As Munford and Walsh-Tapiata (2006) point out, there are many tensions in community development work practice as community organisations strive to understand indigeneity and the meaning of biculturalism. One of the main challenges for Positive Women has been around its capacity to develop a robust Treaty of Waitangi policy and a meaningful bicultural framework in which to engage both its Māori and tauiwi communities.

Recently, Positive Women has been working with Joseph Waru and Kim Penetito, two Māori social practitioners who have engaged in community development and worked in the not-for-profit sector for the past twenty years. Joseph and Kim will be assisting Positive Women to become more actively involved with the Māori community, learn more about Maori protocol and tikanga and create a policy based on the bicultural nature of Aotearoa New Zealand. Munford and Walsh-Tapiata (2006) argue that one of the tasks for community workers is to translate the articles of the Treaty into their daily practices and contextualise the Treaty as a living document that can guide community development practice with diverse populations. Certainly, this is a task that Positive Women is keen to undertake.

Chile (2007a) argues that one of the challenges for community development in Aotearoa New Zealand is to develop empowering practices that encompass the values and goals of a growing multicultural society within a bicultural context. Positive Women’s members represent New Zealand’s multicultural, refugee background and migrant population, and it has been strategic in employing a Rwandan woman, Judith Mukakayange as its Health Promoter. Judith is herself a refugee and a woman living with HIV. Since Judith’s appointment, women who are African migrants and refugees have been more comfortable accessing Positive Women, which is evident in the increasing number of refugee and migrant women who have become members of the organisation. By seeing that ‘one of their own’ is not afraid to be public and speak out about HIV has helped many to become more confident and empowered. Some have started English classes and further training, many have gone to work and integrated more within their communities. Some have left their marriages which were both physically and psychologically abusive, and where HIV was often used to manipulate (J. Bruning, personal communication, May 31, 2016).

A further element of Positive Women’s community vision has been to become more involved in regional networks. It is a member of the Asia Pacific Alliance (APA) and has developed links with the Asia Pacific Network of People Living with HIV (APN+). Jane Bruning was the UNAIDS NGO Delegate for Asia-Pacific throughout 2011-2013. This is an important role, ensuring the priorities and interests of people and communities living with HIV are considered in UNAIDS decisions and policies.

As Positive Women has evolved, its vision has tended to focus more on the conscientisation of the community, particularly through training and educational seminars. Its educational seminars range from personal stories from women living with HIV to the latest information about HIV medications and treatments.6

CURRENT STATE AND FUTURE DIRECTION

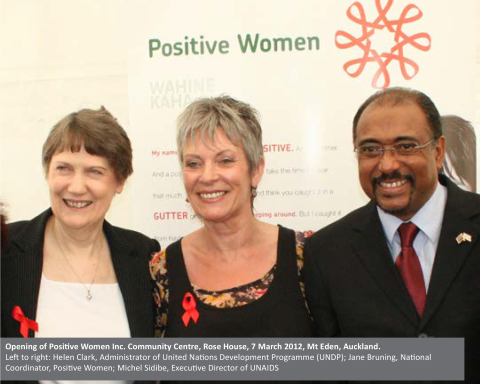

Antiretroviral medication has enabled people living with HIV to live long and fulfilling lives, and mostly remain healthy and strong. Consequently, many of the members of Positive Women have been able to go back to work and do not need the services of Positive Women as much as they did in the past. There are now fewer women dropping in to Positive Women’s Community House, Rose House in Mt Eden, and fewer women are taking advantage of the social events on offer. The decrease in active involvement from Positive Women members can be interpreted as a positive sign. The most effective community development projects make themselves redundant with the outcome that their communities no longer require their support. However, members have made it very clear they want Positive Women to continue to raise awareness about HIV in the community and to focus on reducing HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

Have destigmatisation campaigns worked, or has New Zealand society become less discriminatory? Has internalised stigma decreased after many years of peer support and programmes or have women just lost interest? Anecdotal evidence points to the former, but more research and an exploration of the benefits and ideas for the improvement of the service would provide further insight.

While the support offered to newly diagnosed women remains integral to its vision, the organisation has reached some crossroads. A survey was recently sent out to members to ascertain ways in which Positive Women could continue to support women and families living with HIV. Several members suggested a closed Facebook group where members could have private online chats. It was felt that women in the regions could particularly benefit from such a development. While this initiative was implemented, the group has only around 25 members, with only two of these utilising the chat room on a regular basis (J. Bruning, personal communication, April 22, 2016). While the women do not appear to need the services on a regular basis, anecdotal feedback from members indicate that they see Positive Women as a safety net to turn to in times of need and as a public voice representing women and families in Aotearoa New Zealand living with HIV.

As Haigh (2014) argues, the concept of community is a lasting ideal, from kinship communities through to communities of association. Positive Women is a community development response for women living with HIV that was founded via a community of kinship and association, and its ideals and aspirations remain. New Zealand, as Aimers (2011) reminds us, has an impressive record of women’s involvement in their communities. The challenge for Positive Women is to develop new ways to bring its community together and to continue to focus on those issues that are of paramount importance to women living with HIV and their families. As a viable organisation it continuously evolves with its members’ needs, and as an organisation run by women for women it employs principles of collaboration, partnership, reciprocity and engagement, which are all compatible with community development principles.

CONCLUSION

A community development response to the needs of women and families living with HIV or AIDS provides an important network for women living with HIV to connect and collaborate with their peers, as well as health and other professionals. As Positive Women and other community-based HIV and AIDS service organisations have found, empowerment stems from community development interventions through which community members can develop actions which are culturally and socially relevant to them.

Positive Women carries out what Milner (2008) describes as relational community development practices driven by compassion, which enhances social trust, fairness and justice. Positive Women advocates for greater acceptance and understanding of those affected by HIV. One of its central priorities is to destigmatise HIV and to ensure healthcare workers and members of society in general treat people living with HIV with dignity and respect (Bruning, 2009). As Bruning (2009) states “[t]he involvement of people living with and affected by HIV and AIDS is both paramount and instrumental to all HIV related advocacy, policies and interventions” (p. 113).

Positive Women is a community development intervention that is underpinned by the values and principles espoused by the governance and management of the organisation as directed by the community itself. Its primary objectives have been the enhancement of the wellbeing of women living with HIV and the creation of a community where these women can share their common experiences and have a sense of identity and belonging. Recognising that the wellbeing of the individual is intrinsically connected to the wellbeing of the community (Chile, 2007), Positive Women has not only made a significant difference to the lives of women living with HIV or AIDS, but also to the wider community through its campaigns and promotions. Yet this community is not necessarily a community of choice, but more of circumstances. Because of the way it was developed and managed it became a community of the spirit, where women living with HIV have been able to reach out to one another and find inspiration, courage, friendship and allies.

REFERENCES

AIDS Epidemiology Group. (2009). Retrieved from http://dnmeds.otago.ac.nz/departments/psm/research/aids/epi_surveill.html

AIDS Epidemiology Group. (2016). AIDS-NZ Newsletter. Issue 75. Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Dunedin School of Medicine, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://dnmeds.otago.ac.nz/departments/psm/research/aids/newsletters.html

Aimers, J. (2011). The impact of New Zealand ‘Third Way’ style government on women in community development. Community Development Journal, 46(3), July 302-314.

Bennett, J. (2007). New Zealand women living with HIV/AIDS: A feminist perspective. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 23(1), 4-16.

Bruning, J., Connor, H., & Napan, K. (2013). HIV and AIDS policies globally: A New Zealand perspective. Retrieved from http://unitec.researchbank.ac.nz/handle/10652/3139

Bruning, J. (2007). HIV and stigma: The impact of self stigma on women living with HIV or AIDS. (Unpublished research project, Master of Social Practice). Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand.

Bruning, J. (2009). Stigma and women living with HIV: A co-operative inquiry. (Unpublished Master of Social Practice thesis). Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://unitec.researchbank.ac.nz/handle/10652/1385

Carter, J., Howden-Chapman, P., Park, J., & Scott, K. (1996). An intimate reliance: health reform, viral infection and the safety of blood products. In P. Davis (Ed.), Intimate details and vital statistics: AIDS, sexuality and the social order in New Zealand (pp. 168-184). Auckland, NZ: Auckland University Press.

Chile, L., (2007). Good practice in community development work. In L. Chile (Ed.), Community development practice in New Zealand: Exploring good practice (pp. 21-34). Auckland, NZ: Institute of Public Policy, AUT.

Chile, L., (2007a). The three tikanga of community development in Aotearoa New Zealand. In L. Chile (Ed.), Community development practice in New Zealand: Exploring good practice (pp.35-71). Auckland, NZ: Institute of Public Policy, AUT.

DeMarco, R., & Johnsen, C. (2003). Taking action in communities: Women living with HIV/AIDS lead the way. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 20(1), 51-62.

Padget, A., & Glaser, R. (2003). How stress influences the immune response. TRENDS in Immunology, 24(8), 444-448.

Dickson, N. (1998). AIDS-NZ Newsletter, AIDS Epidemiology Group, (37), 1-4. Retrieved from http:// dnmeds.otago.ac.nz/departments/psm/research/aids/newsletters.html

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York, US: David & Shuster.

Haigh, D. (2014). Community Development and New Zealand local authorities in the 1970s and 1980s. New Zealand Sociology, 29(1), 79-97.

Ife, J., & Fiske, L. (2006). Human rights and community work: Complementary theories and practices. International Social Work, 49(3), 297-308.

INA. (2008). Retrieved from http://www.ina.maori.nz/about.html

MAC AIDS Fund. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.macaidsfund.org/

Mackay, H. (2014). The art of belonging. Sydney, Australia: Macmillan.

McAllister, S. (2009). AIDS New Zealand. Dunedin: Otago University.

McAllister, S. (2011). AIDS New Zealand. Dunedin: Otago University.

Milner, V. (2008). Rekindling the flame of community through compassion – a call for leadership toward compassionate community. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, Issue 3. 3 – 13.

Munford, R., & Walsh-Tapiata, W. (2006). Community development: working in the bicultural context of Aotearoa New Zealand. Community Development Journal, 44 (4). 426-442.

Positive Women. (2012). Positive Women Annual Report. Positive Women Inc. Auckland, NZ: Author. UNAIDS. (2016). Retrieved from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2016/Global-AIDS-update-2016

1 Goffman (1963) used the term ‘spoiled identity’ to describe an identity that causes a person to experience stigma. It is a term which many people who are living with HIV or AIDS use to self-describe their condition.

2 A full list of sponsors of 2 Positive Women can be viewed at: http://www.positivewomen.org.nz/our-sponsors/

3 Body Positive Inc. is a group funded and run for people with HIV/AIDS.

4 NZAF is the New Zealand AIDS Foundation.

5 INA is the Māori, indigenous and South Pacific HIV/AIDS Foundation.