by JENNY AIMERS and PETER WALKER

by JENNY AIMERS and PETER WALKER

Click here to read the pdf

ABSTRACT

In this article we seek to describe the key periods and influences of community development practice in Aotearoa New Zealand. Our historical journey gives particular consideration to the specific impacts the government’s neoliberal policies have had on community development in this country. This work highlights the hostile policy environment that has left community development isolated and unsupported. We also draw on the experience of community development workers from our recent research and reflect on the current position of community development practice in this country and the challenges for its future.

INTRODUCTION

In this paper we describe the key periods of, and influences on, community development practice by building on the historical timeline that was initially developed by Church (2010); incorporating historical work by Chile (2006). We continue the process of storying the practice of community development in Aotearoa New Zealand until 2016. This material is drawn from empirical research undertaken for Aimers & Walker’s 2013 book Community Development: Insights for Practice in Aotearoa New Zealand, combined with a wider literature search. Our historical journey gives particular consideration to the impacts that the government’s neoliberal policies have had on community development. It is our intent in this paper to provide a historical context for current and future practitioners from which they can gain perspective of their own practice. We also consider the commonalities within practice across time, styles and philosophical standpoints. We also hope to stimulate other writers to further research these historical periods in order to offer a more in-depth and critical perspective.

THE HISTORY OF COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND

The special character of community development practice in Aotearoa New Zealand was developed from two distinct cultural origins. Firstly, pre-colonisation, where Māori had a model of society that was communal, holistic and held a sacred relationship with the natural world. Secondly, as the process of colonisation developed in Aotearoa New Zealand during the 1800s, the new immigrants, mainly from the UK, brought with them the charitable models of care and support for the poor and vulnerable within communities that they were familiar with at home. As a result, new groups were established for these purposes, typically under the auspices of the church (Else, 1973; Chile, 2006).

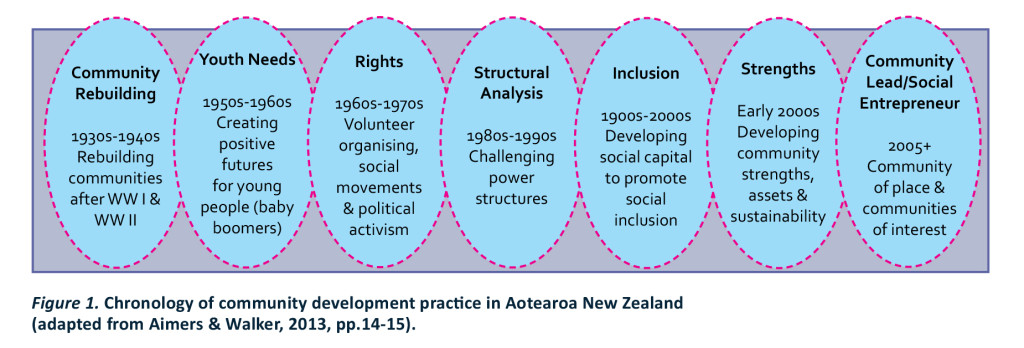

From these two distinct cultural origins, community development practice has been continually influenced by political and social contexts. We outline these various periods and influences briefly, exploring each one to highlight the varied political and social situations that have impacted on community development practice in this country.

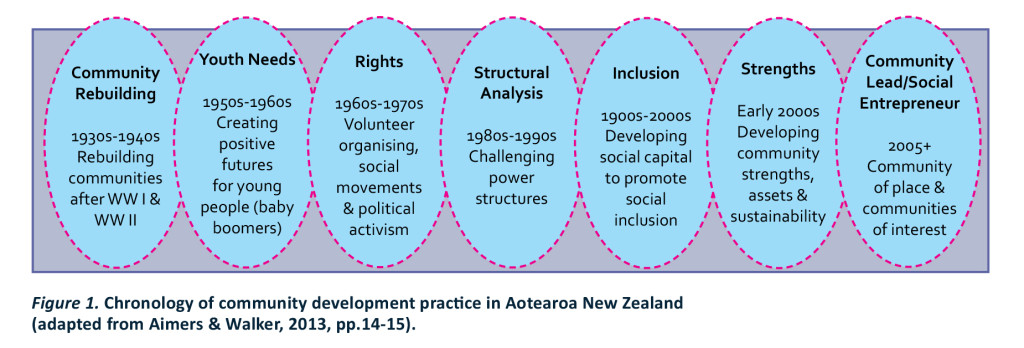

Figure 1 outlines these influences and periods since the 1930s. Note that these influences are highly generalised and represent dominant practices of the time, and do not preclude aspects existing together in subsequent or even preceding phases.

While our focus for this article is on the period from 1980 to the present, we provide a longer historical view, from the 1930s onwards, to give context to this discussion. Despite limited formal professional support for community development in Aotearoa New Zealand, this historical view highlights that there are multiple pathways to development. Applying a broad-brush approach, we outline a progression that begins in the 1930s, becomes more formalised with government programmes in the 1950s, is influenced by consciousness-raising movements in the 1960s and 1970s, moving through the overtly neoliberal political era in the 1980s and its various phases throughout the 1990s and 2000s. These periods encompass capacity building, strengths and community-led approaches and come full circle to the (very different) personal consciousness-raising focus.

COMMUNITY REBUILDING: 1930s-1940s

With the emergence of the welfare state in Aotearoa New Zealand in the 1930s and the introduction of a social democratic polity (Sinclair, 1990), the government focused on improving the physical welfare of individuals. This was undertaken through the provisions of the Physical Welfare & Recreation Act of 1937, which sought to make community recreation more available to prepare healthy young people for the future (including, ironically, the prospect of war), as well as to promote civil bonds. By the late 1940s, disruption and shortages caused by World War Two led to a focus on providing support services and government subsidies. Various Acts of parliament contributed to significant building of community facilities at this time, including the Māori Social and Economic Advancement Act in 1945 and the Department of Internal Affairs War Memorial Hall pound-for-pound subsidy in 1949, that resulted in an extensive network of war memorial community halls and the redevelopment of marae throughout the country (Church, 1990; Stothart 1980, Māori Affairs Department, 1952).

YOUTH NEEDS: 1950s-1960s

After World War Two, urban drift, the baby boom and increasing economic prosperity led to the notion of working to empower groups of people, rather than bestowing charity. New social challenges gave birth to what was termed ‘counter-culture’ movements (Johns, 1993). Rapid urbanisation, post World War Two, particularly for indigenous Māori and immigrants from Pacific Island nations, also created social needs related to housing, health and cultural alienation (Chile, 2006). There was a desire to utilise the increased leisure time of the growing youth population, which resulted in a proliferation of youth and leisure clubs throughout the country (Church, 1990).

RIGHTS: 1960s-1970s

Community development work became recognised as a defined social practice during the 1960s and 1970s. Much of this early community development work was rights-based, responding to the social grassroots movements such as feminism, the Māori renaissance, Pacific peoples’ diaspora and developing youth cultures. Such rights-based work was often undertaken by volunteers rather than paid workers (Vanderpyl, 2004).

The various forms of feminism were hugely significant for women from all types of communities: from solo mothers; Māori women; immigrant women, particularly those originating from the Pacific; through to rural women. Beginning with ‘for women by women’ groups that grew out of the second wave of feminism in the 1970s, consciousness raising and political activity grew into service provision for women run by women in the 1980s and 1990s (Vanderpyl, 2004).

Neighbourhood work also appeared during the 1970s and 1980s as territorial local authorities (TLA) were encouraged to recognise the diversity of their communities and develop community development units under the Local Government Act 1974 (Aimers & Walker, 2013).

STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS: 1980s-1990s

Those working in community development in the late 1970s-1980s may argue that this was a halcyon period for the practice as the rights of social and cultural groupings continued to be debated, and a period of rising inflation, high unemployment and subsequent cuts to state welfare gave fire to the movement. Workers were stimulated by visiting experts; Father Philippe Fanchette appeared during the 1980s and was one of the first to have widespread impact across the county. He was facilitated by John Curnow, a Catholic priest of the Christchurch diocese, who toured Father Fanchette’s workshops around Aotearoa New Zealand. These structural analysis workshops were based on the work of Paolo Freire (1970) and focused on identifying power structures and strategising to reposition power. Structural analysis removed the boundaries between community development agencies and those they worked with, practising a ‘personal is political’ approach. This movement dovetailed with the rights-based work of the previous period and laid a foundation to engage with the emerging issues of the ‘Māori renaissance’ and calls by Māori for te tino rangatiratanga (self-determination), and a call for the Treaty of Waitangi to be honoured as the nation’s founding document. This led to the rise of bi-culturalism as the “…relationship between the state’s founding cultures…” (Durie, 2005). Bi-culturalism in Aotearoa New Zealand has as its basis Te Tiriti o Waitangi /The Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 between the British Crown and Māori. For those working in the wider community this had implications for how they engage with Māori communities, with particular emphasis on understanding the effects of colonisation and how to conduct appropriate consultation on issues that might concern Māori. Likewise, there followed a growing discourse that Māori matters were a subject that required the engagement of Māori researchers.

As in many other countries, the period since the 1980s has been strongly influenced by neoliberal policies that had an unprecedented effect on the community and voluntary sector in Aotearoa New Zealand (Larner & Craig, 2005). With the election of the fourth Labour Government in 1984, Aotearoa New Zealand entered into the neoliberal phase, with the adoption of market-driven policies and the rolling back of the welfare state (Kelsey, 1995). These neoliberal policies effectively ignored community development activities; the government focus towards a social development agenda simply overlooked the role of community development when it did not fit seamlessly into the social development framework.

Larner & Craig (2005) describe the neoliberal period in Aotearoa New Zealand as having three phases: the first phase being the withdrawal of the state from economic production; the second phase being the extension of marketisation and the introduction of neoconservative social policy; and the third phase, a local variant of Tony Blair’s ‘Third Way’ partnership model that saw the introduction of a state-driven partnering ethos by the Labour Government in 1999. The first two phases saw a gradual shift away from grant funding to contracting for services which later led to a further shift to funding for outcomes. This shift to embrace contracting had a great impact on the community and voluntary sector as it established a competition for funding to provide decentralised social services. The policy focus at this time was for social development, and community development all but disappeared from policy as a result. The ‘social development approach’ was designed by the Ministry of Social Development and provided a blueprint for state sector agencies and voluntary agencies to enter into contracting arrangements. Larner (2004, p. 7) defines this approach as a process that brings together the concepts of ‘human capital’ with ‘social capital’ thereby linking communities, families/whanau and individuals to broader economic and social processes. Quoting the New Zealand Prime Minister, Helen Clark, Larner explains that the overall aim of “the social development approach is to ‘reconcile social justice with an energetic and competitive economy’.” This approach led to a standardisation of practice for those community agencies seeking such funded relationships (Harrington, 2005). This shift resulted in resistance and dissatisfaction from the community and voluntary sector to the increasing compliance costs coupled with competitive funding models (Cribb, 2005; Larner & Craig, 2005; Shannon & Walker, 2006).

INCLUSION: 1990s-2000s

The adoption of the social capital rhetoric to bring about social inclusion dominated community development discussion for a number of years from 1990 onwards and was, in part, the basis for the partnering ethos introduced with the adoption of ‘third way-style’ policies by the Labour Government in 1999.

The third phase of neoliberalism focused on partnering, which appeared to align with a communitarian outlook. While the government’s third sector partnering strategy has been described as ‘neo-communitarianism’ this strategy ignored the obvious power imbalance between the two partners. Larner and Butler (2005) observed that community-based yet state-legitimised ‘strategic brokers’ were responsible for the facilitation of the state-community collaboration, thereby blurring the boundaries and distinctions between the community and voluntary sector, and the state.

The third phase of neoliberalism was also influenced by Robert Putnam’s 1995 work linking voluntary association with economic sustainability. This led to a widespread obsession with developing and measuring social capital, particularly at a local government level. This desire was reinforced within the Local Government Act 2002 that required Territorial Local Authorities (TLAs) to promote social, economic, cultural and environmental wellbeing of communities within the development of a ‘long term council community plan’ (Aimers, 2005). As a result of this, the TLAs felt they needed to have a greater awareness of local conditions and issues. This resulted in the development of social indicators that were measured as part of the Quality of Life project, a biennial report published by the largest TLAs collaboratively (Quality of Life Project, 2014). Community development practice and community advisory teams were not universal and had only ever been located in the larger TLAs. The TLAs’ statutory role was vague, “…promoting the social, cultural, environmental and economic well-being of their communities” (Local Government NZ, 2008). TLAs took their lead from central government, focusing on partnering with community groups (Aimers, 2005). Thereby, the TLAs tended to focus on supporting community networks, championing the need for central government resources to their locality, providing small grants to community and sports groups, and supporting central government initiatives to improve community/state relationships, such as Safer Community Councils (to reduce localised crime), Strengthening Families (to better co-ordinate local delivery of family support services) and Road Safety Co-ordination at a local level.

STRENGTHS: EARLY 2000s

These influences of inclusion were followed by a strengths-based approach that focused on localised projects that at times took precedence over structural issues in order to be achievable within defined time frames (Aimers, 2005). This approach was promoted by the Department of Labour’s Community Employment Group who introduced experts in Asset Based Community Development to small towns and rural communities to accompany their Bootstraps programme, which aimed to revitalise depressed or isolated communities. They worked mainly through local authorities to promote Asset Based Community Development utilising a process of mapping community assets that engaged with communities via a stakeholder perspective to identify community projects. In addition, the holistic Global Management Approach (GMA) to community development was promulgated through the Community Employment Group (Aimers & Walker, 2013).

Putman’s version of social capital continued to be influential in this period; defined as social networks, social cohesion and connectedness. For community development practice this segued into a desire by government agencies to build ‘community capacity’ through the development of community networks and voluntary associations, in order to prevent social exclusion (Eketone & Shannon, 2006). The development of social capital to bring about social inclusion dominated community development practice well into the early 2000s. While the social capital rhetoric was attractive to many, Putnam’s version failed to recognise the overt power/political focus of Bourdieu (1986) who viewed capital in all its senses (economic, social and cultural) as a power resource for class conflict. The adoption of Putnam’s form of social capital by local authorities and government agencies conveniently suppressed attention to inequality, conflict and the role of power (Eketone & Shannon, 2006).

Another government focus during this phase was ‘capacity building’, which entailed up-skilling the community and voluntary sector to compete for the delivery of social services. In transferring the provision of social services from the state to the community and voluntary sector, the government wished to ensure high-quality services reflecting the same professional values and accountabilities as the government (Aimers & Walker, 2008; Tennant, O’Brien & Sanders, 2008). Craig and Porter (2006) describe the government policy of the time as “… a strange new hybrid…partnership and competitive contracts, inclusion and sharp discipline, free markets and community…(creating) impossible transaction costs and slippery multilevel accountabilities” (p. 219).

Despite this interest in partnership and community capacity, government support for community development declined during this phase (Aimers & Walker, 2008). Even the terms ‘community development’ or ‘community work’ were subverted, to cover a wide range of activities from non-custodial correctional sentences to beneficiary work schemes. The Community Advisory section of the Department of Internal Affairs, the government department charged with supporting community development, re-focused their Community Development Resource Kit (2003) which subsequently became the Community Resource Kit (2006). Not only was the word development dropped from the title but the community development section was also deleted.

In addition, funding schemes that once supported community development projects were reviewed, resulting in restructuring and refocusing of priorities. One of the most notable casualties of this process was the disestablishment, in 2004, of the Community Employment Group (CEG), which not only meant the loss of funding but also the loss of a dedicated group of advisory staff who worked with communities. The Department of Internal Affairs community-managed funding scheme, the Community Organisations Grants Scheme, that previously had the freedom to fund local priorities along with a unique process for community accountability, was streamlined and standardised to meet government rather than local priorities (Aimers & Walker, 2008).

With no professional body or association to lobby on its behalf, community development effectively went underground – having no place in this newly professionalised sector, and becoming marginalised as a result. Any potential dissenters were occupied by partnering with government as part of the third way agenda (Jenkins, 2005; Larner & Craig, 2005). The partnering process created what Larner and Craig (2005) termed as new governmental spaces and subjects that emerged out of “multiple and contested discourses and practices” (p. 421). They subsequently argued that the only way to resist this new environment was to act locally. While not a defined strategy, this desire to act locally was reflected in the small local projects that subsisted over the late 1990s and early 2000s with little or no government recognition or funding (Larner & Craig, 2005).

The one exception to this generally depressed state of community development was the growth of Māori social service providers, which grew from almost zero to 1000 between 1984 and 2004 (Tennant, O’Brien & Sanders, 2008).

COMMUNITY-LED/SOCIAL ENTREPRENEUR: 2005 ONWARDS

Up until the mid-2000s market driven and neoliberal government policies had had a profound effect on the relationship between the community and voluntary sector and the state, which led to a repositioning of community development so that it effectively disappeared from successive governments’ priorities for support and funding (Aimers & Walker, 2013). These policies have led to a widening gap between larger community and voluntary organisations providing government contracted social services, and those smaller independent community organisations that have not been part of this partnering process (Shannon & Walker, 2006; Tennant, O’Brien & Sanders, 2008). It is mainly with these smaller organisations that the vestiges of bottom-up community development practices that were prevalent in the 1970s and early 1980s have remained.

These sub-cultures of environmentalism, sustainability, alternative lifestyles and social entrepreneurship have, since the 1960s, been strong motivations for community development. These projects have often attracted followers on a very personal level and have been less about changing societal norms and more about creating an alternative to mainstream society.

Since the mid-2000s a new interest in sustainability and sustainable practice has grown, sometimes linked with asset-based community development. The latter has been particularly popular in rural areas and small towns, which have continued to focus on identifying and developing community strengths rather than on social deficits (Aimers & Walker, 2013).

As noted earlier, this time period highlighted the adoption of the third phase of neoliberalism around key rhetorical terms such as ‘partnership’, the legitimation of which has become a major research agenda of a social democratic and centralising government (Craig & Larner, 2002).The dominant governmental discourse during the 2000s became that of social development rather than community development. This was an attempt to counter the fragmentation of social services that had occurred as a result of the competitive contracting model (Shannon & Walker, 2006). Although community development did not disappear, for the next 10 years or so it continued without much access to central government funding or support.

However, one significant area of advancement at this time was Māori development; The movement for indigenous (Māori) development grew in parallel to non-Māori community development models by creating new perspectives based within Māori communities (Eketone, 2006; Eketone, 2013) as well as influencing the process of Pākehā engaging with Māori communities.

Māori development focuses on a decolonising and self-determining agenda that separates Māori development from other forms of community development. Māori development has its own theoretical background that reflects a uniquely Māori perspective on notions of identity and community, expressed in multiple forms. These forms include Māori community development (social justice), Iwi development (tribal-based economic development), Marae development (upholding the mana or reputation of the Marae or hapū i.e., local tribal group) and positive Māori development (political advancement and self-determination) (Eketone, 2013). Eketone highlights the complexity and pluralistic nature of tribal-based Māori communities, with their own unique histories, values and perspectives that make it difficult to ascribe a unitary explanation. Perhaps one of the key knowledges is the Māori focus on process as an outcome in itself: “If you have maintained a project where people have pulled together, had a satisfying involvement and finished with their mana intact, then that is good – the community has been strengthened” (Eketone, 2013, p. 197).

For community development as a whole, the non-profit organisation Inspiring Communities Trust, after a decade or more of being supported primarily by volunteerism, with little available funding, can be credited with bringing community development back to the attention of government. Inspiring Communities promoted a single specific method of community development, termed community-led development. While this method was first cited in the 2005 report from the Department of Internal Affairs, Investing in Community Capacity Building, it was not until the establishment of the Inspiring Communities Trust that community-led development began to gain traction. Community-led development is characterised as a place-based practice that seeks to develop local resources and strengths by nurturing a whole-of-community shared vision (Inspiring Communities, 2010). It must be noted, however, that while community-led development gained a lot of currency, it was not the only form of community development being practised in this period. One project in particular was held up to represent the spirit of community-led development in the early stages, the Victory Village project in Nelson. The Victory Village project sought to identify community aspirations that form the basis for collaboration amongst community members and various health and welfare professionals. The project addressed local problems by changing the underlying system in which a problem lies; they called this process ‘social innovation’ (Stuart, 2010). It captured significant government interests, so much so that a national Victory Village forum was held in 2011, supported by Inspiring Communities and the Government’s Families Commission.

WHERE IS COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT IN 2016?

Currently the government support for community and voluntary sector grants (including community development) totals a just over $18 million per annum, compared with $300 million for the newly established Community Investment social service contracts (Harwood, 2016). Included in the former are two government-administered grant funding programmes related to community development. Crown Grants that “…support local initiatives, projects, activities and community services” (Community Matters, 2015, p. 1), covering projects including community development and Lottery Grants. The Department of Internal Affairs also offers a community advisory service to “…provide advice, information, support and resources to assist the development of resilient and prosperous communities, hapū and iwi” (Community Matters, 2015, p. 1). From the Crown funding pool, a much smaller pilot programme was established in 2011 that redirected $1.5 million of community organisation grant funding to trial a new form of funding allocation for community-led development. This funding was allocated to five community-based fund holders to run community-led development process within their communities. They were tasked to allocate this funding in response to a broad-based community visioning and planning process (Turia, 2011b). In her report to the Cabinet Social Policy Committee, the architect of this initiative, the Hon Tariana Turia, stated, “I want to see a shift of focus in my portfolio away from small grants for individual projects and/or service organisations towards a community-led development (CLD) approach which invests more directly and more strategically in communities as a whole to achieve better outcomes for those communities” (Turia, 2011a). The pilot period was initially from July 2011 to June 2015; it has since been extended with four of the original providers (one has dropped out), and funded with an additional $400,000 until June 2016 (Department of Internal Affairs, 2015).

Support for the CLD trial was provided by Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) community advisors trained in community-led development principles. Inspiring Communities (2010) argue that significant social transformation requires acting across multiple parts of a system. This approach, however, is not easy to implement and relies on developing a commitment to the overarching interests of a geographic locality, which may cut across interests of personal identity. The most recent evaluation of the pilot found that overall the outcomes were positive but that the community-led approach was demanding and at times had “…a negative effect on the enthusiasm and pace in which CLD projects are carried out” (Department of Internal Affairs, 2015, p. 6). It was also found that the multiple accountabilities to the funder and the communities created an element of top-down between the department and the communities, and groups felt constrained by the milestones. Some groups also struggled to achieve the ‘whole of community’ consensus that was required by the community-led approach, particularly those with larger more diverse populations (Department of Internal Affairs, 2013).

Continuing the desire to pursue a public-private partnership, the government has also started to explore the notion of social enterprise, with a nationwide survey to discover the nature and extent of social enterprise activity through the Department of Internal Affairs (Munro, 2012) followed by the establishment of a business-style social enterprise incubator trial. Major philanthropic funders, the Tindall and Todd Foundations, have also promoted the development of social enterprise through their joint initiative, the Ākina Foundation, which, while still very much in its infancy, focuses on activities that have a business model that can deliver social or environmental impact (Culpan, 2015).

Our empirical research of those practising community development (Aimers & Walker, 2013) found that respondents were not necessarily tied to the government viewings of community development practice. In fact only a few of our respondents had consciously chosen to do ‘community development work’ and some did not want to be labelled ‘community development workers’, but instead chose other titles such as facilitators, project workers, field officers or community workers. Many of the projects came into being as a result of dissatisfaction with government provision and consequently have existed without government support. Many respondents, irrespective of the era they practised in, spoke of government not understanding their perspective and not being willing to listen. It is not surprising therefore that all the respondents shared a belief in the importance of a communitarian process and thinking. These were influenced by myriad philosophical approaches from neo-peasantry to tourism-destination management. It was surprising, however, to find that despite these fundamental differences, the processes they developed (often in isolation) for achieving change in their respective communities were alike, irrespective of the time period or the community context. The community development tools used by our respondents can be summarised as:

- “Engaging your community by cultivating a shared vision and building trust

- Keeping things going with effective communication and facilitation

- Finding ways of getting stuff done using activities and practical projects

- Empowering and ensuring succession by cultivating new leaders”

(Aimers & Walker, 2013, p. 173)

These processes match those outlined in a multitude of community development resources and as such reinforce what is considered to be appropriate community development practice internationally. This commonality does suggest that in general, there is something constant and enduring in the practice and considering few had sought qualifications in community development. For those who did seek qualifications there were few alternatives to choose from. It is indicative of the current position of community development in Aotearoa New Zealand that, other than a community development major in the Bachelor of Social Practice offered at Unitec Institute of Technology in Auckland, there are no stand-alone educational qualifications available for those wishing to study community development in Aotearoa New Zealand. Some community development workers we interviewed sought further education in allied fields such as social work, community recreation, health promotion and geography (Aimers & Walker, 2013). These various fields consequently provide alternative perspectives that influence the multiplicity of community development practice in Aotearoa New Zealand.

CONCLUSION

The special character of community development work in Aotearoa New Zealand has been inspired by a range of styles or practices, including neighbourhood development, structural analysis, social capital-building, strengths-based practice, asset-based community development, Māori development, sustainable development, social entrepreneurship and, most recently, community-led development. Despite a shift in government funding priorities towards social development and the needs of individuals, a commitment to some form of communitarian community development practice remains. Recently there has been an increased government interest in community development, evidenced by CLD and social enterprise projects. However, from the evaluation reports of the CLD trial it appears that communities have had difficulties in engaging with CLD practice. Our research (Aimers & Walker, 2013) found that that many community development practitioners resisted applying for government funding in order to have the freedom to practise in a manner that is appropriate to their community context, that may or may not follow the dominant community development practice mode of the moment.

Having been driven almost underground during the 1990s and early 2000s, new practitioners are now taking up the reins with limited resources and somewhat isolated from the wisdom gained by previous generations. Despite this, we found that many of the tools used in earlier times have not changed. Some styles and standpoints remain rooted to particular periods, yet community work practice in 1980 has more in common with practice in 2016 than is immediately obvious. Whether the work they undertake is to support and build localised community relationships or challenge the existing social order at a political level, the tools used are similar across time and practice. These tools can be summarised as: engaging your community by cultivating a shared vision and building trust; using communication and facilitation to keep things going; getting stuff done via some form of practical achievement; and bringing new leaders forward to ensure succession for your project.

The underground nature of communitarian practice has meant that there is little recorded history of this work. We hope that by offering this overview we can stimulate further study and in-depth analysis of the history of community development in Aotearoa New Zealand. There are many more stories still to be told, and further reflection on lessons learned, that would benefit new practitioners. In order to grow, however, community development practice in Aotearoa New Zealand needs to be viewed as a pluralist, rather than a singular way of working. For example, community development practice may have to eschew the very label community development in order to avoid the connotations with specific (historical) models of practice. While governments may still seek to define and support a particular way of working, what seems to work best is when communities resist those approaches and seek their own community-derived solutions. Many challenges remain however, including the need to educate practitioners. For those who seek community development training, there need to be appropriate educational opportunities developed that also support community-centred knowledge and an experiential base that models a wide range of practices and perspectives. In addition, to fund community development activities, government and philanthropic sectors need to create funding models with community-based accountabilities that ensure that such work is embedded within and responsive to the communities where it is located.

REFERENCES

Aimers, J. (2005). Developing community partnerships: social wellbeing and the Local Government Act 2002. Social Work Review, 17(3), pp. 34-40.

Aimers, J. & Walker, P. (2013). Community development: Insights for practice in Aotearoa New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Dunmore Press.

Aimers, J. & Walker, P. (2008). Is community accountability a casualty of government partnering in New Zealand? Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work Review, 20(3), pp. 14-24.

Bourdieu, P. (1986) The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (New York, Greenwood), pp. 241-258.

Chile, L. (2006). The historical context of community development in Aotearoa New Zealand. Community Development Journal, 41(4), pp. 407-425.

Church, A. (1990). Community Development. Monograph Series 13, Research Unit, Department of Internal Affairs. Wellington, NZ: Department of Internal Affairs.

Department of Internal Affairs. (2015). Community matters: Funding and grants. Retrieved from http://www.communitymatters.govt.nz/Funding-and-grants—All-of-our-grant-funding

Craig, G. (2005, December). Community capacity building: Definitions, scope, measurements and critiques. Paper prepared for the OECD, Prague, Czech Republic. Retrieved from http://www.iacdglobal.org/files/OECDcomcapbldg102007.pdf

Craig, D. & Larner, W. (2002). Local Partnerships and Social Governance in Aotearoa New Zealand. Strengthening Communities Through Local Partnerships Symposium. Auckland, NZ: University of Auckland.

Craig, D. & Porter, D. (2006). Development beyond neoliberalism? Governance, poverty reduction and political economy. London, UK: Routledge.

Cribb, J. (2005). Accounting for something: voluntary organisations, accountability and the implications for government funders. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand Te Puna Whakaaro, 26, November 2005. Retrieved from https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-journal/spj26/26-pages43-51.pdf on 8/07/2016.

Culpan, A. (2015). Social enterprise Aotearoa: Insights and opportunities (Research report). Retrieved from https://annetteculpan.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/social-enterprise-aotearoa-insights1.pdf

Department of Internal Affairs. (2006). The community development resource kit. Retrieved from www.community.net.nz/how-toguides/crk

Department of Internal Affairs. (2008). Ministerial briefing papers. Retrieved from http://www.beehive.govt.nz/sites/all/files/DIA_BIM.pdf

Department of Internal Affairs. (2013). Community-led development year 2 evaluation report. Wellington, NZ: Author. Retrieved from http://www.dia.govt.nz/pubforms.nsf/URL/CLD-Year-2-evaluation-report-Dec-2013.pdf/$file/CLD-Year-2-evaluation-report-Dec-2013.pdf 21/05/2013

Department of Internal Affairs. (2015). Community-led development year 3 evaluation report. Wellington, NZ: Author. Retrieved from http://www.dia.govt.nz/pubforms.nsf/URL/CLD-Year-3-evaluation-report-Final.pdf/$file/CLD-Year-3-evaluation-report-Final.pdf accessed from 8/05/2015.

Durie, M. (2005, July). The rule of law, biculturalism and multi-culturalism. Paper presented at ALTA

Conference, University of Waikato. Retrieved from http://www.lawcom.govt.nz/sites/default/files/speeches/2005/07/ALTA%20conference%20-%20July%202005%20-%20Durie. pdf 10/11/14

Eketone, A. (2013). Māori development and Māori communities. In J. Aimers & P. Walker (Eds.), Community development: insights for practice in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 185-199). Auckland, New Zealand: Dunmore Press

Eketone, A. (2006). Tapuwae: a vehicle for community change. Community Development Journal, 41(4), pp.467-480.

Eketone, A. & Shannon, A. (2006). Community development: Strategies for empowerment in a sustainable Aotearoa/New Zealand. In C. Freeman & M. Thompson-Fawcett (Eds.), Living together: Towards inclusive communities (pp. 207-227). Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago Press.

Else, A. (1973). Women together, a history of women’s organisations in New Zealand. Wellington, NZ: Daphne Brasell Associates Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, US: Herder and Herder.

Harrington, P. (2005). Partnership work. Research Paper No. 17, Strengthening Communities through Local Partnerships Programme, University of Auckland.

Harwood, B. (2016, March 27). Measure results, MSD boss says. Otago Daily Times. Retrieved from http://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/377582/measure-results-msd-boss-says

Inspiring Communities. (2010). What are we learning about community-led development in Aotearoa New Zealand. Inspiring Communities. December 2010.

Jenkins, K. (2005). No way out? Incorporating and restructuring the voluntary sector within spaces of neo-liberalism. In N. Laurie & L. Bondi (Eds.), Working the spaces of neo-liberalism (pp.216-221). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Johns, K. (1993). Community development in territorial local authorities: A profile. Wellington, NZ: Department of Internal Affairs.

Kelsey, J. (1995). The New Zealand experiment – a world model for structural adjustment? London, UK and East Haven, US: Pluto Press.

Larner, W. (2004). Neoliberalism in (regional) theory and practice: The Stronger Communities Action Fund, Research Paper No. 14, Strengthening Communities through Local Partnerships Programme, University of Auckland.

Larner, W. & Craig, D. (2005). After neoliberalism? Community activism and local partnerships in Aotearoa New Zealand. Antipode, 37, 402-424. doi: 10.1111/j.0066-4812.2005.00504.x

Local Government NZ. (2008). Role of Local Government. Local Government New Zealand. Retrieved from www.lgnz.govt.nz/lg-sector/role/ [accessed 4 May 2009]

Maori Affairs Department. (1952). The Story of the Modern Marae. Te Ao Hou 2. Spring 1952, 23-23. Retrieved from www.teaohou.natlib.govt.nz/jounrals/teaohou/issue/Maoo2TeA/ci14.html [accessed 6 July 2016]

Munro, B. (2012, November 3). Making a difference. Otago Daily Times. p. 45-47.

Putnam, R.D. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), pp. 65-78.

Quality of life project. (2014). Retrieved from http//:www.qualityoflifeproject.govt.nz

Stuart, D. (2010). Paths of victory: Victory Village (Victory Primary School and Victory Community Health Centre) – A case study. (New Zealand Families Commission, Innovative Practice Fund Report No. 8/10). Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Government.

Shannon, P. & Walker, P. (2006). Inclusion and autonomy in state-local partnerships participation and control in a state/local partnership in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Community Development Journal, 14, pp. 506-520.

Sinclair, K. (Ed.). (1990). The Oxford illustrated history of New Zealand (second edition). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Stothart, R. (1980). The new deal in recreation and sport in J. Shallcrass R. Larkin and R. Stothart (eds) Recreation Reconsidered into the Eighties, Wellington:Auckland Regional Authority New Zealand Council for Recreation and Sport, pp. 47-54

Tennant, M., O’Brien, M., & Sanders, J. (2008). The history of the non-profit sector in New Zealand. Wellington, NZ: Office for the Community and Voluntary Sector. Retrieved from http://www.ocvs.govt.nz/documents/publications/reports/the-history-of-the-non-profit-sector-in-new-zealand.pdf

Turia, T. (2011a). Budget 2011 – new initiative to support community-led development (Press Release). Retrieved from http://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/budget-2011-new-initiative-support-community-led-development 21/05/2013

Turia, T. (2011b). Progress Implementing the Community-led Development Approach, Report to the Cabinet Social Policy Committee from the Office of the Minister for the Community and

Voluntary Sector. 31 August 2011, Retrieved from http://www.dia. govt.nz/Pubforms.nsf/ URL/Cabinet_Paper_ProgressImplementingThe Community-ledDevelopmentApproach.pdf/$file/Cabinet_Paper_Progress ImplementingTheCommunity-ledDevelopmentApproach.pdf on 19/8/ 2015).

Vanderpyl, J. (2004). Aspiring for unity and equality: Dynamics of conflict and change in the ‘by women for women’ feminist service groups, Aotearoa/New Zealand (1970-1999). (Unpublished PhD thesis). University of Auckland.

Save

Save