This week I went down to French Pass, to help plan the implementation of one of the most ambitious predator eradication programs suggested in New Zealand. This narrow channel separating D’Urville Island from the South Island is possibly the most spectacular (and dangerous) stretch of water in New Zealand, and hopefully it will soon be the moat that helps protect one of our largest predator free islands.

D’Urville Island/Rangitoto ki te Tonga (16,782ha) is the eighth-largest of New Zealand’s offshore islands, and is nationally significant for its diverse geology, relatively intact and diverse plant communities, and high number of nationally-threatened, rare or unusual species. A suite of mammalian pests found on the mainland are absent from the island, including ship rats, Norway rats, brushtail possums and feral goats. Because of the reduced pest suite, the island holds many important populations of threatened species including the New Zealand falcon, marsh crake, giant land snails, skinks and geckos, and in particular it has the largest population of long-tailed bats in the South Island. There are however kiore, mice, stoats and feral cats, which have led to the recent decline of bird species, and the local extirpation of kiwi, kaka and kakariki.

The D’Urville Island Stoat Eradication Charitable Trust (DISECT) was formed in 2004 to promote the concept of stoat eradication on D’Urville Island, and after 14 years of planning and consultation, there is now support from all residents to achieve this goal. If successful this program would make it the largest successful stoat eradication ever attempted in the world.

For me this meeting was not just an opportunity to help plan the project and get a better understanding of the challenges faced here, but it was also a great chance to catch up with old friends and colleagues – many of whom are world leaders in eradication planning such as John Parkes, Dan Tompkins and Peter McMurtrie. For a project this large and complex, every aspect, logistical, ecological and social needs to be planned in detail. Hopefully we will soon publish the results of our discussion to show the reasoning behind the many planning decisions.

So how will this eradication be done?

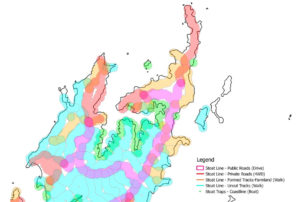

The residents of the island have opted to do the eradication without toxins – using trapping alone. I should note that I support the use of toxins for many eradications, and that toxins such as brodifacoum are extremely useful and have many benefits, but as the community wishes to attempt this project without their use, this is how we will proceed. It will require traps to be spread across the island at unprecedented densities. Therefore, a dense network of traps is planned, making sure that every stoat home range has at least one trap in it.

Figure 1 Map of the northern half of D’Urville Island showing trap locations surrounded by 350 m buffers.

So let’s say that we can remove all of the stoats, what then?

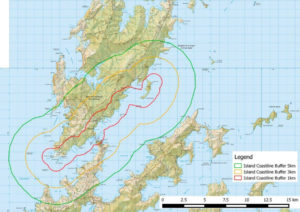

As MacBeth said “To be thus is nothing, but to be safely thus…” Once the stoats are eradicated, we need to keep them off the island. Stoats are phenomenal swimmers – something I’ve researched in depth, and that is how they arrived on the island originally. While the currents through French Pass are strong, with swirling whirlpools and eddies, obviously they are not enough to keep the stoats permanently at bay. Therefore, the plan is to have traps (and potentially fences) to remove all of the stoats along the potential invasion front. As there is the possibility of stoats swimming up to 5 km, we are planning on trapping all land out to this distance on the mainland.

Figure 2 Map showing the putative swimming distances for stoats to the island

One of the important things that we need to do is measure invasion rates to the island – how often do stoats make it across that swirling water? This will help determine how many, and the spacing of traps both on the mainland and on the island. I am currently helping lead an analysis using genetics to see how all of the stoats are related to each other. Once we can look at relatedness patterns among the stoats in the region, we can see how many swim across – basically detecting siblings, parents, aunts, uncles etc on each side. Detecting a relative that swam is much easier than sticking tags on lots of stoats and hoping you catch the one that swims across!

There is still a lot of planning to do, and continuing discussions to be had with the community, local iwi, and funders, but a solid plan is forming that will hopefully lead to a successful campaign to remove these voracious predators. Once they are removed, many endangered species such as rowi, little spotted kiwi and kakariki can be reintroduced. When I started my PhD I had no idea I would spend the next decade of my life helping to apply my research to conservation programs – and getting the opportunity to visit some spectacular places in the process. Cheers to Dave, Andrew, Pip and everyone else involved for inviting me down there!

Contact

Dr Andrew Veale

aveale@unitec.ac.nz

Leave a Reply